How to prevent Vault privilege escalation?

The Problem: Privilege Escalation

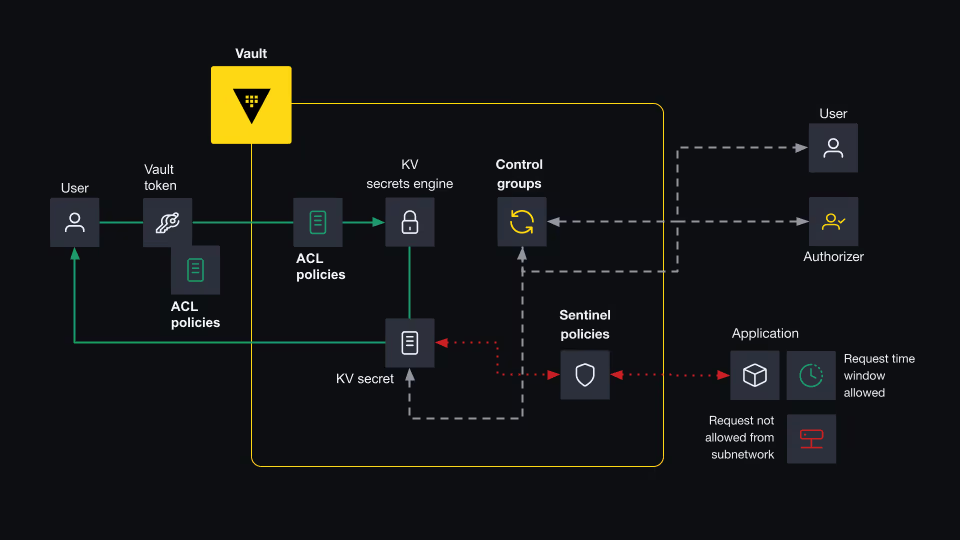

How can we be certain that Hashicorp Vault holding precious information is truly secure? How can we trust that the policies won’t have unintended, dangerous consequences tomorrow?

The answer, lies not in hope, but in proof. Today, I would like to take you on a journey into a world where we can use the pristine power of mathematics to verify our work and build systems that are provably trustworthy. We will explore a beautiful concept called Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) and use it to solve a very real-world challenge: securing HashiCorp Vault policies by denying privilege escalation.

From Boolean Logic (SAT) to Rich Theories (SMT)

At the heart of Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) is a simpler problem called SAT, or the Boolean Satisfiability Problem.

-

SAT (The Foundation): Imagine you have a complex logical formula with only

True/Falsevariables, connected byAND,OR, andNOT. For example:(A OR B) AND (NOT A OR C). The SAT problem asks: “Can you find a combination ofTrueandFalsevalues for A, B, and C that makes the whole formulaTrue?” A program that solves this is called a SAT solver. -

SMT (The Superpower): SMT, or Satisfiability Modulo Theories, takes this to a whole new level. It asks the same fundamental question but allows the variables to be much more than just

TrueorFalse. It reasons about them “modulo” (or “in the context of”) different mathematical theories.

Z3 is one of the world’s most advanced SMT solvers developed by Microsoft. It’s the engine that understands these theories (integers, real numbers, arrays, strings, bitvectors, and more) and can answer that fundamental question: “Can a state of the world exist where all these complex constraints are satisfied?”

A Conversation with an Oracle of Logic

Let’s start with a simple conversation. Imagine we tell Z3:

Oh, Z3, I am thinking of two numbers,

xandy. All I know is thatx + y = 20, and also thatxmust be greater than15.

Can we find such numbers?

Let’s ask Z3 in its native tongue (Python).

import z3

# Declare our two unknown numbers

x = z3.Int('x')

y = z3.Int('y')

# Create our solver, our oracle

solver = z3.Solver()

# Add our statements (constraints)

solver.add(x + y == 20)

solver.add(x > 15)

# Ask the oracle if a solution exists

print(solver.check())

# If a solution exists, ask for an example

if solver.check() == z3.sat:

print(solver.model())Z3 will reply:

sat

[y = 4, x = 16]

The word sat is short for “satisfiable.”

It means, “Yes, a world exists where all your statements are true.”

The model [y = 3, x = 17] is a concrete example from that world.

Now, what if we add one more rule: y must also be greater than 15?

# ... (previous code)

solver.add(y > 15) # Our new, impossible constraint

print(solver.check())Z3 will now reply: unsat.

It has mathematically proven that no such numbers can possibly exist.

This power to prove both the possible and the impossible is what makes Z3 so profound.

From Numbers to Paths: The Language of Vault

Now, how does this connect to securing Vault?

Vault policies control access based on paths, like file paths on a computer.

For example, a policy might grant access to secret/app/db.

The challenge arises with Vault’s powerful wildcards:

+matches a single path segment.secret/+/dbwould matchsecret/app/dbbut notsecret/app/v1/db.*matches anything, even multiple segments.secret/app/*would match bothsecret/app/dbandsecret/app/db/table.

For a human, reviewing dozens of these rules can be bewildering. For Z3, it’s just another logical puzzle. We can translate these path patterns into Z3’s language of regular expressions.

Let’s see how. We can write a small translator function. Don’t worry about the details of the code; focus on the beautiful transformation from a policy string into a logical object.

import z3

import re

from z3 import InRe, Re, Range, String, StringVal

def vault_path_to_z3_regex(path: str) -> z3.ReRef:

"""Converts a Vault path string into a Z3 regular expression."""

# The '*' wildcard translates to '.*' in regex (any character, any number of times)

# The '+' wildcard is trickier: it means 'any characters except a slash'

re_parts = []

def wildcard_ranges():

return [

Range('a', 'z'), Range('A', 'Z'), Range('0', '9'),

Re(StringVal('-')), Re(StringVal('_')), Re(StringVal('.'))

]

for part in re.split(r'([+]|\*$)', path):

if part == '*':

wildcard_regex = z3.Star(z3.Union(*wildcard_ranges(), Re(StringVal('/'))))

re_parts.append(wildcard_regex)

elif part == '+':

re_parts.append(z3.Plus(z3.Union(*wildcard_ranges())))

else:

re_parts.append(Re(StringVal(part)))

if len(re_parts) < 2:

return re_parts[0]

return z3.Concat(re_parts)

# Example Usage:

path_pattern = "secret/app/*"

z3_regex = vault_path_to_z3_regex(path_pattern)

print(f"The Vault path '{path_pattern}' becomes the Z3 regex: {z3_regex}")Now Z3 understands what secret/app/* means.

We can ask it questions!

For example: “Does the path secret/app/db match the pattern secret/app/*?”

# Declare an unknown string variable for the path we are checking

input_path = z3.String('input_path')

# Create the constraint

path_matches_pattern = z3.InRe(input_path, z3_regex)

# Ask Z3 if our example 'secret/app/db' satisfies the constraint

solver = z3.Solver()

solver.add(path_matches_pattern)

solver.add(input_path == z3.StringVal("secret/app/db"))

print(solver.check()) # This will print 'sat'The Ghost in the Machine: Finding Privilege Escalation

Here is the heart of our exploration. Privilege escalation happens when a change to a policy accidentally grants more access than intended. For example, a developer might want to add a new, specific rule but uses a broad wildcard by mistake.

How can we find this “ghost in the machine”? We can ask Z3 a very precise, philosophical question:

Wise Z3, can you find me a single path that is ALLOWED by the NEW policy, but was DENIED by the OLD policy?

If Z3 says sat and gives us an example, we have found a privilege escalation!

Let’s translate this into Z3’s logic.

new_policy= A path is allowed by the new rules.old_policy= A path is allowed by the old rules.Not(old_policy)= A path is denied by the old rules.

Our query to Z3 is: And(new_policy, Not(old_policy))

Let’s try it with a real example.

- Old Policy: Access is granted to

secret/app/prodonly. - New Policy: Access is granted to

secret/app/*.

# Our unknown input path

input_path = z3.String('input_path')

# 1. Define the old and new policies in Z3's language

old_policy_regex = vault_path_to_z3_regex("secret/app/prod")

new_policy_regex = vault_path_to_z3_regex("secret/app/*")

old_policy_match = z3.InRe(input_path, old_policy_regex)

new_policy_match = z3.InRe(input_path, new_policy_regex)

# 2. Formulate our philosophical question

escalation_found = z3.And(new_policy_match, z3.Not(old_policy_match))

# 3. Ask Z3

solver = z3.Solver()

solver.add(escalation_found)

print(f"Checking for escalation... {solver.check()}")

if solver.check() == z3.sat:

print("Escalation detected! Here is an example:")

print(solver.model())Z3 will reply:

Checking for escalation... sat

Escalation detected! Here is an example:

[input_path = "secret/app/d"]

Look at that! Z3 didn’t just tell us there was a problem; it gave us a concrete example.

The path secret/app/d (and many others like secret/app/dev) is now allowed where it wasn’t before.

We have found the ghost.

Completing the Picture: Paths and Capabilities

Our logic can be made even richer. Vault policies have at least two parts: the path and the capabilities (like read, write, delete).

A user needs both to match.

Let’s expand our model to check for an escalation where a user is granted a new capability on an existing path.

- Old Policy:

secret/app/db->["read"] - New Policy:

secret/app/db->["read", "write"]

The question is the same, but our definition of “policy” is now more complete.

# Declare unknown inputs for path and capability

input_path = z3.String('path')

input_cap = z3.String('cap')

# --- Old Policy Definition ---

# Path must be 'secret/app/db' AND capability must be 'read'

old_policy_match = z3.And(

input_path == "secret/app/db",

input_cap == "read"

)

# --- New Policy Definition ---

# Path must be 'secret/app/db' AND capability must be 'read' OR 'write'

new_policy_match = z3.And(

input_path == "secret/app/db",

z3.Or(

input_cap == "read",

input_cap == "write"

)

)

# --- The Escalation Check ---

solver = z3.Solver()

solver.add(z3.And(new_policy_match, z3.Not(old_policy_match)))

print(f"Checking for escalation... {solver.check()}")

if solver.check() == z3.sat:

print("Escalation detected! Here is the exact path and capability:")

print(solver.model())And Z3, our faithful oracle, will reveal the truth:

Checking for escalation... sat

Escalation detected! Here is the exact path and capability:

[cap = "write", path = "secret/app/db"]

It has precisely identified the escalation: the write capability was added to the secret/app/db path.

The Path Priority: Teaching the Oracle to Think Like Vault

Our journey into proof has been fruitful.

We’ve taught our Z3 oracle to understand paths and capabilities, and we’ve given it a profound question to find privilege escalation: And(new_policy, Not(old_policy)).

But a new, more subtle question arises, one that strikes at the heart of intent and ambiguity.

What happens when policies overlap?

When a single request for a path like secret/app/db matches multiple rules, which one should apply?

Imagine a policy set with these two rules:

secret/app/*->["read"]secret/app/db->["create"]

A developer requests read access to secret/app/db.

Both rules match this path.

Does the user get read access, create access, both, or none?

A simple logical OR is insufficient; it would grant both, which is not how Vault behaves.

This is not just a technical challenge; it’s philosophical. How do we teach our logical oracle to infer the administrator’s true intent?

The answer lies in a principle that governs many human systems: specificity. Vault assumes that the most specific rule is the one that reflects the most specific intent. It has a clear, deterministic hierarchy to resolve this ambiguity, and to build a true verifier, we must encode this knowledge into our model. We must teach the oracle to think like Vault.

Let’s explore this hierarchy, rule by rule, as implemented in our compare_path_priority function.

Rule 1: The First Wildcard

The Rule: “If the first wildcard (+) or glob (*) occurs earlier in P1, P1 is lower priority.” The longer the literal prefix of a path, the more specific its intent.

The Code:

# From compare_path_priority

first_wildcard1 = first_wildcard_pos(path1)

first_wildcard2 = first_wildcard_pos(path2)

if (first_wildcard1 is not None and first_wildcard2 is not None

and first_wildcard1 != first_wildcard2):

# The path with the wildcard appearing later has higher priority.

return int(first_wildcard1 - first_wildcard2)Example:

path1 = "secret/+/db"(wildcard at index 7)path2 = "secret/app/*"(wildcard at index 11)- Result:

secret/app/*has higher priority because its wildcard appears later.

Rule 2: The Open-Ended Glob *

The Rule: “If P1 ends in * and P2 doesn’t, P1 is lower priority.” A path ending in * is inherently open-ended and less specific than a path that names a final segment.

The Code:

# From compare_path_priority

ends_with_star1 = path1.endswith('*')

ends_with_star2 = path2.endswith('*')

if ends_with_star1 != ends_with_star2:

return -1 if ends_with_star1 else 1Example:

path1 = "secret/app/*"path2 = "secret/app/db"- Result:

secret/app/dbhas higher priority because it does not end with a*.

Rule 3: The Cost of a +

The Rule: “If P1 has more + (wildcard) segments, P1 is lower priority.” Vault penalizes paths that use the segment-wildcard more frequently, favoring those with fewer “unknowns.”

The Code:

# From compare_path_priority

plus_count1 = path1.count('+')

plus_count2 = path2.count('+')

if plus_count1 != plus_count2:

return plus_count2 - plus_count1Example:

path1 = "secret/+/+/data"(2 pluses)path2 = "secret/app/+/data"(1 plus)- Result:

secret/app/+/datahas higher priority because it has fewer+wildcards.

Rule 4 & 5: The Tie-Breakers

The Rule: When ambiguity can no longer be resolved by structure, Vault falls back on two simple, deterministic tie-breakers: path length and then alphabetical order.

The Code:

# From compare_path_priority

# Rule 4: Path length

if len(path1) != len(path2):

return len(path1) - len(path2)

# Rule 5: Lexicographic comparison

if path1 < path2:

return -1Example (Length):

path1 = "secret/a"path2 = "secret/long"- Result:

secret/longhas higher priority because it is longer.

Example (Lexicographical):

path1 = "secret/a"path2 = "secret/b"- Result:

secret/bhas higher priority because “b” comes after “a” alphabetically.

Putting It All Together: A Complete Example

Let’s see how this intricate logic synthesizes into a correct verdict. Consider this policy:

rules = {

"secret/*": ["read"],

"secret/app/db": ["create", "update"],

"secret/+/db": ["read", "delete"]

}A request comes in to delete the path secret/app/db. Which rule applies?

secret/*matches. It allowsread.secret/app/dbmatches. It allowscreate,update.secret/+/dbmatches. It allowsread,delete.

Our build_policy_allow function first uses compare_path_priority to sort these matching paths from highest to lowest priority:

secret/app/db(longest, no wildcards)secret/+/db(wildcard at index 7)secret/*(wildcard at index 7, but ends in*)

It then constructs a nested If-Then-Else expression in Z3 that mirrors this priority:

# Conceptual Z3 logic

If(input_path matches "secret/app/db",

# Highest priority rule applies

(input_cap == "create" or input_cap == "update"),

# Else, check the next rule

If(input_path matches "secret/+/db",

(input_cap == "read" or input_cap == "delete"),

# Else, check the last rule

If(input_path matches "secret/*",

(input_cap == "read"),

# Default deny if no rules match

False

)

)

)Now, let’s run the full check in code to see the outcome.

import z3

# Assuming policy_checker.py is available

from policy_checker import build_policy_allow

# 1. Define the rules and the request

rules = {

"secret/*": ["read"],

"secret/app/db": ["create", "update"],

"secret/+/db": ["read", "delete"]

}

request_path = "secret/app/db"

request_cap = "delete"

# 2. Create Z3 variables and the policy expression

input_path = z3.String('path')

input_cap = z3.String('cap')

is_allowed = build_policy_allow(input_path, input_cap, rules)

# 3. Formulate the question to Z3

solver = z3.Solver()

# Is it possible for the request to be allowed under the policy?

solver.add(is_allowed)

solver.add(input_path == request_path)

solver.add(input_cap == request_cap)

# 4. Ask the oracle and print the result

result = solver.check()

print(f"Is '{request_path}' with '{request_cap}' allowed? {result}")

# --- Let's try another capability ---

solver.reset()

request_cap_denied = "read"

solver.add(is_allowed)

solver.add(input_path == request_path)

solver.add(input_cap == request_cap_denied)

result_denied = solver.check()

print(f"Is '{request_path}' with '{request_cap_denied}' allowed? {result_denied}")Execution Output:

Is 'secret/app/db' with 'delete' allowed? unsat

Is 'secret/app/db' with 'read' allowed? unsatThe oracle correctly says unsat (not satisfiable) for both delete and read

Why? Because for the path secret/app/db, the highest priority rule is the exact match secret/app/db, which only grants create and update.

All other matching rules, like secret/+/db (which would have allowed delete), are ignored due to their lower priority.

This is the power of encoding the knowledge of priority. Our verifier doesn’t just see a collection of rules; it sees the hierarchy, the intent, and provides a provably correct answer based on the same logic Vault itself would use.

The Final Word: Explicit Deny

So far, we have untangled the sophisticated path priority for allow rules.

We’ve taught our oracle to weigh and measure paths, selecting the single most specific rule to grant capabilities.

But Vault has one final, powerful tool in its arsenal: the deny capability.

And its logic is simple.

An explicit deny on any matching path always takes precedence.

This rule acts as a definitive veto.

It doesn’t matter if a high-priority allow rule perfectly matches a path; if even a low-priority, broadly-scoped rule issues a deny for that same path, access is rejected.

Think of it as two separate checks:

- The

allowcheck: Is there anallowrule that grants the requested capability? This involves the entire priority comparison we’ve detailed. Z3 finds the single highest-priority matching rule. - The

denycheck: Is there anydenyrule that matches the requested path? This is a simpleORacross all deny policies; priority is irrelevant.

For a request to succeed, the answer to the first question must be “yes,” AND the answer to the second must be “no.”

In Z3, this translates to a beautifully clean final formula:

And(is_allowed_by_priority, Not(is_denied_by_any))

Let’s see this absolute power in action.

Example 1: The Simple Veto

This is the most straightforward case.

- Policy:

{"secret/app/db": ["read", "deny"]} - Request:

readonsecret/app/db. - Logic: The path matches, and the capabilities include both

readanddeny. Thedenyacts as an instant override. - Result: Access denied.

Example 2: The Priority Override

This is where the true power of deny becomes clear. It ignores the priority ladder that allow rules must climb.

- Policy:

{"secret/app/*": ["deny"], "secret/app/db": ["read"]} - Request:

readonsecret/app/db. - Logic:

- Allow Check: The

allowrulesecret/app/dbis a higher priority for the path thansecret/app/*. So, theallowcheck passes. - Deny Check: The

denyrulesecret/app/*also matches the pathsecret/app/db.

- Allow Check: The

- Result: Because a matching

denyrule exists, access is denied, even though theallowrule was more specific.

Grand Finale: Modeling the Veto in Code

Let’s construct a final, complete scenario that models this interaction.

We will define a policy where a specific allow should be overridden by a general deny.

import z3

from policy_checker import build_policy_allow

# 1. Define the rules and the contentious request

rules = {

# Broad rule that denies everything under secret/app/

"secret/app/*": ["deny"],

# Specific rule that allows 'create' on a subpath

"secret/app/db": ["create"]

}

request_path = "secret/app/db"

request_cap = "create"

# 2. Create Z3 variables and the full policy expression

input_path = z3.String('path')

input_cap = z3.String('cap')

# The build_policy_allow function now internally handles the

# And(allow_logic, Not(deny_logic))

is_allowed = build_policy_allow(input_path, input_cap, rules)

# 3. Formulate the question to Z3

solver = z3.Solver()

# Is it possible for the 'create' request to be allowed?

solver.add(is_allowed)

solver.add(input_path == request_path)

solver.add(input_cap == request_cap)

# 4. Ask the oracle for its final verdict

result = solver.check()

print(f"Is '{request_path}' with '{request_cap}' allowed? {result}")

# --- Let's check a path that ISN'T denied ---

solver.reset()

rules_new = {

"secret/app/*": ["deny"],

"secret/data/db": ["read"] # This path is not under secret/app/*

}

is_allowed_new = build_policy_allow(input_path, input_cap, rules_new)

solver.add(is_allowed_new)

solver.add(input_path == "secret/data/db")

solver.add(input_cap == "read")

result_new = solver.check()

print(f"Is 'secret/data/db' with 'read' allowed? {result_new}")Execution Output:

Is 'secret/app/db' with 'create' allowed? unsat

Is 'secret/data/db' with 'read' allowed? satThe oracle’s conclusion is definitive and correct.

The request to create at secret/app/db is unsat because, despite the high-priority allow rule, the lower-priority deny from secret/app/* casts the final, deciding vote.

However, a request for a path completely untouched by the deny rule is correctly found to be sat.

By modeling this final piece of Vault’s logic, our verifier achieves a true, high-fidelity representation. It understands the nuances of specificity, the hierarchy of intention, and the absolute authority of a denial, allowing it to explore policy interactions with the same logical rigor as Vault itself.

All the code was published on Github in the repository dangerousplay/vault-policy-checker.

You can see more examples of privilege escalation in the escalation tests.

What Else Can We Do With This Power?

The “truth-seeking” power of SMT solvers like Z3 is used across the entire field of computing. The Vault policy checker is just one example. Here are some others:

-

Automated Test Case Generation: You can describe the logic of a function to Z3 and ask it to find inputs that trigger a specific bug. For example: “Find me an integer

xthat causes this function to divide by zero.” Z3 will try to solve for a value ofxthat makes the divisor expression equal to zero. -

Software and Hardware Verification: Before shipping a product, companies like Microsoft, Intel, and Amazon use SMT solvers to formally prove that their code or chip designs are free of certain classes of critical bugs, such as buffer overflows, deadlocks, or race conditions.

-

Planning and Scheduling: You can model a complex scheduling problem (e.g., scheduling classes in rooms, tasks on factory machines) as a set of constraints and ask the solver: “Does a valid schedule exist that respects all constraints (time, resources, dependencies)?” If it says

sat, the model it provides is the valid schedule. -

Network Configuration Analysis: You can model all the firewall and routing rules in a network as logical statements. Then you can ask the solver critical security questions like, “Is there any path by which an external actor can reach our internal database server?”

-

Cryptography and Security: Researchers use SMT solvers to analyze cryptographic protocols and find logical flaws or vulnerabilities that might be missed by human inspection.

In essence, if you can describe your problem in terms of rules and constraints, you can use an SMT solver to find solutions, prove that no solution exists, or find corner cases you never thought of. It’s a foundational tool for building more reliable, secure, and correct systems.

Future Work

- Integration with HashiCorp Vault API for direct policy extraction

- GUI for visualizing policy coverage and potential violations

A More Hopeful Horizon

We began with a question of trust, and using pure logic we found an answer to a complex problem that was proved using math. We can proof that the new policy does not give more privileges than the current one removing any scenario for privilege escalation. Which is truly amazing considering how difficult it would be to proof the logic of an algorithm to do the same without using SMT.

I hope you have enjoyed this journey. I’m always open to contribute, to receive feedback. If you have suggestions, improvements, I’m all ears.

Have a wonderful day, shine bright ^^

Sources

The thumbnail image is from Hashicorp Documentation Why use Vault